Richard's September Update

Sep 30, 2020Cancellation in Beast/Asio and Better Compile Performance with Beast.Websocket

This month I will be discussing two issues. One of interest to many people who come to us with questions on the Github Issue Tracker and the #beast channel of Cpplang Slack.

Compile Times and Separation of Concerns

A common complaint about Boost.Beast is that compilation units that use the websocket::stream template class

often take a long time to compile, and that because websocket::stream is a template, this compilation overhead can

become viral in an application.

This is a valid complaint and we believe there are some reasonable tradeoffs we can make by refactoring the websocket stream to use fewer templates internally. Vinnie has started work to express the WebSocket’s intermediate completion handlers, buffer sequence and executor in terms of a polymorphic object. This would mean a few indirect jumps in the compiled code but would significantly reduce the number of internal template expansions. In the scheme of things, we don’t believe that the virtual function calls will materially affect runtime performance. The branch is here

I will be continuing work in this area in the coming days.

In the meantime, our general response is to suggest that users create a base class to handle the transport, and communicate important events such as frame received, connection state and the close notification to a derived application-layer class through a private polymorphic interface.

In this way, the websocket transport compilation unit may take a while to compile, but it needs to be done only once since the transport layer will rarely change during the development life of an application. Whenever there is a change to the application layer, the transport layer is not affected so websocket-related code is not affected.

This approach has a number of benefits. Not least of which is that developing another client implementation over a different websocket connection in the same application becomes trivial.

Another benefit is that the application can be designed such that application-level concerns are agnostic of the transport mechanism. Such as when the server can be accessed by multiple means - WSS, WS, long poll, direct connection, unix sockets and so on.

In this blog I will present a simplified implementation of this idea. My thanks to the cpplang Slack user @elegracer

who most recently asked for guidance on reducing compile times. It was (his/her? Slack is silent on the matter) question

which prompted me to finally conjure up a demo. @elegracer’s problem was needing to connect to multiple cryptocurrency

exchanges in the same app over websocket. In this particular example I’ll demonstrate a simplified connection to

the public FMex market data feed since that was the subject of the original question.

Correct Cancellation

Our examples in the Beast Repository are rudimentary and don’t cover the issue of graceful shutdown of an application in response to a SIGINT (i.e. the user pressing ctrl-c). It is common for simple programs to exit suddenly in response to this signal, which is the default behaviour. For many applications, this is perfectly fine but not all. We may want active objects in the program to write data to disk, we may want to ensure that the underlying websocket is shut down cleanly and we may want to give the user an opportunity to prevent the shutdown.

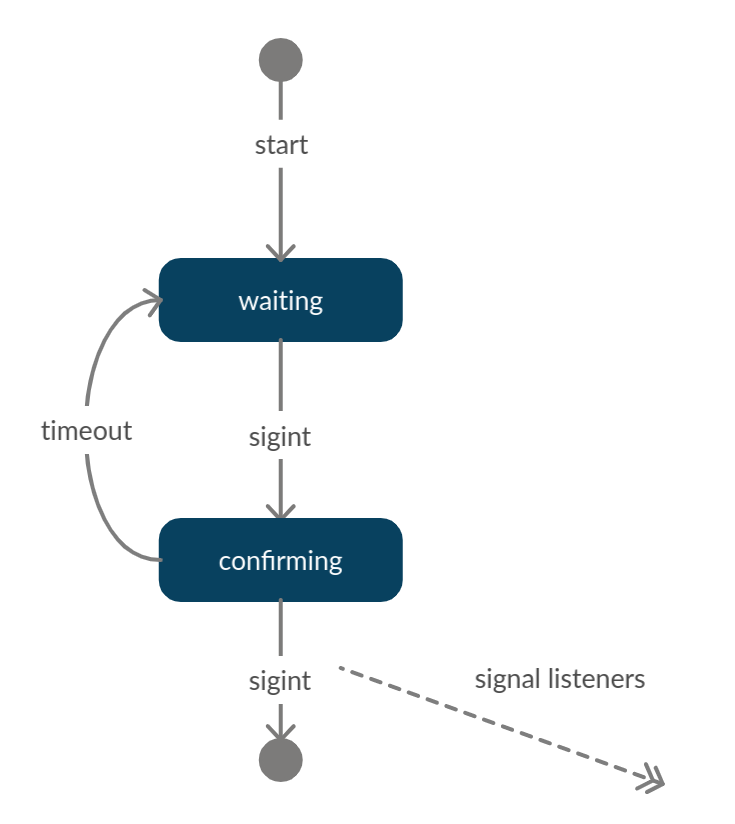

I will further annotate the example by providing this ability to prevent the shutdown. The user will have to confirm the first SIGINT with another within 5 seconds to confirm.

Designing the application

When I write IO applications involving Asio and Beast, I prefer to create an “application” object. This has the responsibility of monitoring signals and starting the initial connection objects. It also provides the communication between the two.

The construction and configuration of the io_context and ssl::context stay in main(). The executor and ssl context

are passed to the application by reference as dependencies. The application can then pass on these refrences as

required. It is also worth mentioning that I don’t pass the io_context’s executor as a polymorphic any_io_executor

type at this stage. The reason is that I may want in future to upgrade my program to be multi-threaded. If I do this,

then each individual io_enabled object such as a connection or the application will need to have its own strand.

Getting the strand out of an any_io_executor is not possible in the general case as it will have been type-erased, so

for top level objects I pass the executor as io_context::executor_type. It is then up to each object to create its own

strand internally which will have the type strand<io_context::executor_type>. The strand type provides the method

get_inner_executor which allows the application to extract the underlying io_context::executor_type and pass it to

the constructor of any subordinate but otherwise self-contained io objects. The subordinates can then build their own

strands from this.

Step 1 - A Simple Application Framework That Supports ctrl-c

OK, let’s get started and build the framework. Here’s a link to step 1.

ssl.hpp and net.hpp simply configure the project to use boost.asio. The idea of these little configuration headers

is that they could be generated by the cmake project if necessary to allow the option of upgrading to std networking

if it ever arrives.

As a matter of style, I like to ensure that no names are created in the global namespace other than main. This saves

headaches that could occur if I wrote code on one platform, but then happened to port it to another where the name

was already in use by the native system libraries.

main.cpp simply creates the io execution context and a default ssl context, creates the application, starts it and

runs the io context.

At the moment, the only interesting part of our program is the signit_state. This is a state machine which handles the

behaviour of the program when a SIGINT is received. Our state machine is doing something a little fancy. Here is the

state diagram:

Rather than reproduce the code here, please refer to step 1 to see the source code.

At this point the program will run and successfully handle ctrl-c:

$ ./blog_2020_09

Application starting

Press ctrl-c to interrupt.

^CInterrupt detected. Press ctrl-c again within 5 seconds to exit

Interrupt unconfirmed. Ignoring

^CInterrupt detected. Press ctrl-c again within 5 seconds to exit

^CInterrupt confirmed. Shutting down

Step 2 - Connecting to an Exchange

Now we need to create our WebSocket transport class and our FMex exchange protocol class that will derive from it. For now we won’t worry about cancellation - we’ll retrofit that in Step 3.

Here is the code for step 2.

This section introduces two new main classes - the wss_transport and the fmex_connection. In addition, the connection

phase of the wss_transport is expressed as a composed operation for exposition purposes (and in my opinion it actually

makes the code easier to read than continuation-passing style code)

Here is the implementation of the connect coroutine:

struct wss_transport::connect_op : asio::coroutine

{

using executor_type = wss_transport::executor_type;

using websock = wss_transport::websock;

Here we define the implementation of the coroutine - this is an object which will not be moved for the duration of the execution of the coroutine. This address stability is important because intermediate asynchronous operations will rely on knowing the address of the resolver (and later perhaps other io objects).

struct impl_data

{

impl_data(websock & ws,

std::string host,

std::string port,

std::string target)

: ws(ws)

, resolver(ws.get_executor())

, host(host)

, port(port)

, target(target)

{

}

layer_0 &

tcp_layer() const

{

return ws.next_layer().next_layer();

}

layer_1 &

ssl_layer() const

{

return ws.next_layer();

}

websock & ws;

net::ip::tcp::resolver resolver;

net::ip::tcp::resolver::results_type endpoints;

std::string host, port, target;

};

The constructor merely forwards the arguments to the construction of the impl_data.

connect_op(websock & ws,

std::string host,

std::string port,

std::string target)

: impl_(std::make_unique< impl_data >(ws, host, port, target))

{

}

This coroutine is both a composed operation and a completion handler for sub-operations. This means it must have an

operator() interface matching the requirements of each sub-operation. During the lifetime of this coroutine we

will be using the resolver and calling async_connect on the tcp_stream. We therefore provide conforming member

functions which store or ignore the and forward the error_code to the main implementation of the coroutine.

template < class Self >

void

operator()(Self & self,

error_code ec,

net::ip::tcp::resolver::results_type results)

{

impl_->endpoints = results;

(*this)(self, ec);

}

template < class Self >

void

operator()(Self &self, error_code ec, net::ip::tcp::endpoint const &)

{

(*this)(self, ec);

}

Here is the main implementation of the coroutine. Note that the last two parameters provide defaults. This is in order to allow this member function to match the completion handler signatures of:

void()- invoked during async_compose in order to start the coroutine.void(error_code)- invoked by the two functions above and by the async handshakes.void(error_code, std::size_t)- invoked by operations such as async_read and async_write although not strictly necessary here.template < class Self > void operator()(Self &self, error_code ec = {}, std::size_t = 0) {Note that here we are checking the error code before re-entering the coroutine. This is a shortcut which allows us to omit error checking after each sub-operation. This check will happen on every attempt to re-enter the coroutine, including the first entry (at which time

ecis guaranteed to be default constructed).if (ec) return self.complete(ec); auto &impl = *impl_;Note the use of the asio yield and unyield headers to create the fake ‘keywords’

reenterandyieldin avery limited scope.#include <boost/asio/yield.hpp> reenter(*this) { yield impl.resolver.async_resolve( impl.host, impl.port, std::move(self)); impl.tcp_layer().expires_after(15s); yield impl.tcp_layer().async_connect(impl.endpoints, std::move(self)); if (!SSL_set_tlsext_host_name(impl.ssl_layer().native_handle(), impl.host.c_str())) return self.complete( error_code(static_cast< int >(::ERR_get_error()), net::error::get_ssl_category())); impl.tcp_layer().expires_after(15s); yield impl.ssl_layer().async_handshake(ssl::stream_base::client, std::move(self)); impl.tcp_layer().expires_after(15s); yield impl.ws.async_handshake( impl.host, impl.target, std::move(self));If the coroutine is re-entered here, it must be because there was no error (if there was an error, it would have been caught by the pre-reentry error check above). Since execution has resumed here in the completion handler of the

async_handshakeinitiating function, we are guaranteed to be executing in the correct executor. Therefore we can simply callcompletedirectly without needing to post to an executor. Note that theasync_composecall which will encapsulate the use of this class embeds this object into a wrapper which provides theexecutor_typeandget_executor()mechanism which asio uses to determine on which executor to invoke completion handlers.impl.tcp_layer().expires_never(); yield self.complete(ec); } #include <boost/asio/unyield.hpp> } std::unique_ptr< impl_data > impl_; };

The wss_connection class provides the bare bones required to connect a websocket and maintain the connection. It

provides a protected interface so that derived classes can send text frames and it will call private virtual functions

in order to notify the derived class of:

- transport up (websocket connection established).

- frame received.

- connection error (either during connection or operation).

- websocket close - the server has requested or agreed to a graceful shutdown.

Connection errors will only be notified once, and once a connection error has been indicated, no other event will reach the derived class.

One of the many areas that trips up asio/beast beginners is that care must be taken to ensure that only one async_write

is in progress at a time on the WebSocket (or indeed any async io object). For this reason we implement a simple

transmit queue state which can be considered to be an orthogonal region (parallel task) to the read state.

// send_state - data to control sending data

std::deque<std::string> send_queue_;

enum send_state

{

not_sending,

sending

} send_state_ = not_sending;

You will note that I have used a std::deque to hold the pending messages. Although a deque has theoretically better

complexity when inserting or removing items at the ends than a vector, this is not the reason for choosing this data

structure. The actual reason is that items in a deque are guaranteed to have a stable address, even when other items

are added or removed. This is useful as it means we don’t have to move frames out of the transmit queue in order to

send them. Remember that during an async_write, the data to which the supplied buffer sequence refers must have a

stable address.

Here are the functions that deal with the send state transitions.

void

wss_transport::send_text_frame(std::string frame)

{

if (state_ != connected)

return;

send_queue_.push_back(std::move(frame));

start_sending();

}

void

wss_transport::start_sending()

{

if (state_ == connected && send_state_ == not_sending &&

!send_queue_.empty())

{

send_state_ = sending;

websock_.async_write(net::buffer(send_queue_.front()),

[this](error_code const &ec, std::size_t bt) {

handle_send(ec, bt);

});

}

}

void

wss_transport::handle_send(const error_code &ec, std::size_t)

{

send_state_ = not_sending;

send_queue_.pop_front();

if (ec)

event_transport_error(ec);

else

start_sending();

}

Finally, we can implement our specific exchange protocol on top of the wss_connection. In this case, FMex eschews

the ping/pong built into websockets and requires a json ping/pong to be initiated by the client.

void

fmex_connection::ping_enter_state()

{

BOOST_ASSERT(ping_state_ == ping_not_started);

ping_enter_wait();

}

void

fmex_connection::ping_enter_wait()

{

ping_state_ = ping_wait;

ping_timer_.expires_after(5s);

ping_timer_.async_wait([this](error_code const &ec) {

if (!ec)

ping_event_timeout();

});

}

void

fmex_connection::ping_event_timeout()

{

ping_state_ = ping_waiting_pong;

auto frame = json::value();

auto &o = frame.emplace_object();

o["cmd"] = "ping";

o["id"] = "my_ping_ident";

o["args"].emplace_array().push_back(timestamp());

send_text_frame(json::serialize(frame));

}

void

fmex_connection::ping_event_pong(json::value const &frame)

{

ping_enter_wait();

}

Note that since we have implemented frame transmission in the base class in terms of a queue, the fmex class has no need to worry about ensuring the one-write-at-a-time rule. The base class handles it. This makes the application developer’s life easy.

Finally, we implement on_text_frame and write a little message parser and switch. Note that this function may throw.

The base class will catch any exceptions thrown here and ensure that the on_transport_error event will be called at

the appropriate time. Thus again, the application developer’s life is improved as he doesn’t need to worry about

handling exceptions in an asynchronous environment.

void

fmex_connection::on_text_frame(std::string_view frame)

try

{

auto jframe =

json::parse(json::string_view(frame.data(), frame.size()));

// dispatch on frame type

auto &type = jframe.as_object().at("type");

if (type == "hello")

{

on_hello();

}

else if (type == "ping")

{

ping_event_pong(jframe);

}

else if (type.as_string().starts_with("ticker."))

{

fmt::print(stdout,

"fmex: tick {} : {}\n",

type.as_string().subview(7),

jframe.as_object().at("ticker"));

}

}

catch (...)

{

fmt::print(stderr, "text frame is not json : {}\n", frame);

throw;

}

Compiling and running the program produces output similar to this:

Application starting

Press ctrl-c to interrupt.

fmex: initiating connection

fmex: transport up

fmex: hello

fmex: tick btcusd_p : [1.0879E4,1.407E3,1.0879E4,2.28836E5,1.08795E4,1.13E2,1.0701E4,1.0939E4,1.0663E4,2.51888975E8,2.3378048830533768E4]

fmex: tick btcusd_p : [1.08795E4,1E0,1.0879E4,3.79531E5,1.08795E4,3.518E3,1.0701E4,1.0939E4,1.0663E4,2.51888976E8,2.3378048922449758E4]

fmex: tick btcusd_p : [1.0879E4,2E0,1.0879E4,3.7747E5,1.08795E4,7.575E3,1.0701E4,1.0939E4,1.0663E4,2.51888978E8,2.3378049106290182E4]

fmex: tick btcusd_p : [1.0879E4,2E0,1.0879E4,3.77468E5,1.08795E4,9.229E3,1.0701E4,1.0939E4,1.0663E4,2.5188898E8,2.337804929013061E4]

fmex: tick btcusd_p : [1.0879E4,1E0,1.0879E4,1.0039E4,1.08795E4,2.54203E5,1.0701E4,1.0939E4,1.0663E4,2.51888981E8,2.3378049382050827E4]

Note however, that although pressing ctrl-c is noticed by the application, the fmex feed does not shut down in response.

This is because we have not wired up a mechanism to communicate the stop() event to the implementation of the

connection:

$ ./blog_2020_09

Application starting

Press ctrl-c to interrupt.

fmex: initiating connection

fmex: transport up

fmex: hello

fmex: tick btcusd_p : [1.0859E4,1E0,1.0859E4,6.8663E4,1.08595E4,4.1457E4,1.07125E4,1.0939E4,1.0667E4,2.58585817E8,2.3968266005011003E4]

^CInterrupt detected. Press ctrl-c again within 5 seconds to exit

fmex: tick btcusd_p : [1.08595E4,2E0,1.0859E4,5.9942E4,1.08595E4,4.3727E4,1.07125E4,1.0939E4,1.0667E4,2.58585819E8,2.3968266189181537E4]

^CInterrupt confirmed. Shutting down

fmex: tick btcusd_p : [1.08595E4,2E0,1.0859E4,5.9932E4,1.08595E4,4.0933E4,1.07125E4,1.0939E4,1.0667E4,2.58585821E8,2.396826637335208E4]

fmex: tick btcusd_p : [1.0859E4,1E0,1.0859E4,6.2722E4,1.08595E4,4.0943E4,1.07125E4,1.0939E4,1.0667E4,2.58585823E8,2.3968266557531104E4]

fmex: tick btcusd_p : [1.08595E4,1.58E2,1.0859E4,6.2732E4,1.08595E4,3.7953E4,1.07125E4,1.0939E4,1.0667E4,2.58585981E8,2.3968281107003917E4]

^Z

[1]+ Stopped ./blog_2020_09

$ kill %1

[1]+ Stopped ./blog_2020_09

$

[1]+ Terminated ./blog_2020_09

Step 3 - Re-Enabling Cancellation

You will remember from step 1 that we created a little class called sigint_state which notices that the application

has received a sigint and checks for a confirming sigint before taking action. We also added a slot to this to pass the

signal to the fmex connection:

fmex_connection_.start();

sigint_state_.add_slot([this]{

fmex_connection_.stop();

});

But we didn’t put any code in wss_transport::stop. Now all we have to do is provide a function object within

wss_transport that we can adjust whenever the current state changes:

// stop signal

std::function<void()> stop_signal_;

void

wss_transport::stop()

{

net::dispatch(get_executor(), [this] {

if (auto sig = boost::exchange(stop_signal_, nullptr))

sig();

});

}

We will also need to provide a way for the connect operation to respond to the stop signal (the user might press ctrl-c while resolving for example).

The way I have done this here is a simple approach, merely pass a reference to the wss_transport into the composed

operation so that the operation can modify the function directly. There are other more scalable ways to do this, but

this is good enough for now.

The body of the coroutine then becomes:

auto &impl = *impl_;

if(ec)

impl.error = ec;

if (impl.error)

return self.complete(impl.error);

#include <boost/asio/yield.hpp>

reenter(*this)

{

transport_->stop_signal_ = [&impl] {

impl.resolver.cancel();

impl.error = net::error::operation_aborted;

};

yield impl.resolver.async_resolve(

impl.host, impl.port, std::move(self));

//

transport_->stop_signal_ = [&impl] {

impl.tcp_layer().cancel();

impl.error = net::error::operation_aborted;

};

impl.tcp_layer().expires_after(15s);

yield impl.tcp_layer().async_connect(impl.endpoints,

std::move(self));

//

if (!SSL_set_tlsext_host_name(impl.ssl_layer().native_handle(),

impl.host.c_str()))

return self.complete(

error_code(static_cast< int >(::ERR_get_error()),

net::error::get_ssl_category()));

//

impl.tcp_layer().expires_after(15s);

yield impl.ssl_layer().async_handshake(ssl::stream_base::client,

std::move(self));

//

impl.tcp_layer().expires_after(15s);

yield impl.ws.async_handshake(

impl.host, impl.target, std::move(self));

//

transport_->stop_signal_ = nullptr;

impl.tcp_layer().expires_never();

yield self.complete(impl.error);

}

#include <boost/asio/unyield.hpp>

The final source code for step 3 is here.

Stopping the program while connecting:

$ ./blog_2020_09

Application starting

Press ctrl-c to interrupt.

fmex: initiating connection

^CInterrupt detected. Press ctrl-c again within 5 seconds to exit

^CInterrupt confirmed. Shutting down

fmex: transport error : system : 125 : Operation canceled

And stopping the program while connected:

$ ./blog_2020_09

Application starting

Press ctrl-c to interrupt.

fmex: initiating connection

fmex: transport up

fmex: hello

^CInterrupt detected. Press ctrl-c again within 5 seconds to exit

fmex: tick btcusd_p : [1.0882E4,1E0,1.0882E4,3.75594E5,1.08825E4,5.103E3,1.07295E4,1.0939E4,1.06785E4,2.58278146E8,2.3907706652603207E4]

^CInterrupt confirmed. Shutting down

closing websocket

fmex: closed

Future development

Next month I’ll refactor the application to use C++20 coroutines and we can see whether this makes developing event based systems easier and/or more maintainable.

Thanks for reading.

All Posts by This Author

- 08/10/2022 Richard's August Update

- 10/10/2021 Richard's October Update

- 05/30/2021 Richard's May 2021 Update

- 04/30/2021 Richard's April Update

- 03/30/2021 Richard's February/March Update

- 01/31/2021 Richard's January Update

- 01/01/2021 Richard's New Year Update - Reusable HTTP Connections

- 12/22/2020 Richard's November/December Update

- 10/31/2020 Richard's October Update

- 09/30/2020 Richard's September Update

- 09/01/2020 Richard's August Update

- 08/01/2020 Richard's July Update

- 07/01/2020 Richard's May/June Update

- 04/30/2020 Richard's April Update

- 03/31/2020 Richard's March Update

- 02/29/2020 Richard's February Update

- 01/31/2020 Richard's January Update

- View All Posts...